Ada Kaleh: the Missing Island

Lying three kilometers downstream of Orşova, the island was swallowed by the Danube’s waters in 1970.

28 Mai 2011, 12:10

Translated, the name ‘Ada Kaleh’ means the citadel island, or the fortress island.

In 1970, the island was swallowed by the Danube’s waters, following the construction of the Iron Gate I.

Until then, though, it had been what the former inhabitants, as well as those visiting the island, called ‘Heaven on Earth’.

From one end to the other, it was no more than 2000 meters long and 500 wide, and the 1930 census showed that 450 people were living on Ada Kaleh at that time, the majority of whom were Turks.

Audio: the documentary ‘Ada Kaleh: the Missing Island’, Radio România Actualităţi, the 6th of August, 2010.

‘Miniature Istanbul’

A police station was built on Ada Kaleh during the interwar years, but no crimes were ever reported, in any historical document. To be more precise, in the island’s only monograph, written by the imam Ali Ahmed, this is what was mentioned: ‘No brawls or murders ever took place’.

The island enjoyed an almost Mediterranean weather. That is what explains the fact that on the island one could find figs the size of a fist, olive trees and oleander. There, they drank Turkish coffee, and the figs and roses preserves, as well as the Turkish delight, were true delicacies. Ada Kaleh was a sort of floating Istanbul, a small Orient on the Danube.

Because of its strategic position, the island always attracted the interest of the great powers during WWI, having been either under Austrian or Ottoman ruling. In the 18th century, the Austrians built an imposing fortification on Ada Kaleh, based on the renowned Vauban system, with thick walls and tunnels.

Defensive purpose

Later on, the island was colonized by the Turks and the buildings changed their purpose. The Austrian headquarters became a mosque, and the people built houses on the walls. Consequently, the Citadel Island became a place with a unique architecture.

After WWI, in 1921 to be more precise, after a referendum, the inhabitants of the island decided that the island itself and the people living on it should become part of Romania.

There was a school on the island, where people studied both in Romanian as well as in Turkish. There were also a town hall, the imposing houses of Ali Kadri, the richest man on the island, a dispensary, a gendarme’s office, and a police station.

You could also find a cinema where – some locals say – a film would run for an entire month, so that one would end up learning it by heart.

Foto: The interior of a Turkish house from the Ada Kaleh island, reconstructed at the Iron Gates Region Museum

Notable guests

In 1929, Ada Kaleh was visited by King Carol II and Nicolae Iorga, who brought a series of gifts, such as a large quantity of sugar, from which the locals made the famous Turkish sweets (baklava, lokum and fig and rose preserves).

It was then when the Romanian authorities decided that the traditional products that were made on the island (among which there were also seventeen types of cigarettes), should be tax-free

During the last years, the number of tourists, whom the island locals called ‘visitors’, increased considerably.

The island was also visited by the renowned journalist Felix Brunea Fox, who wrote an exposé about the richest man on the island, Ali Kadri, whom, it seemed, the locals had accused of different abuses.

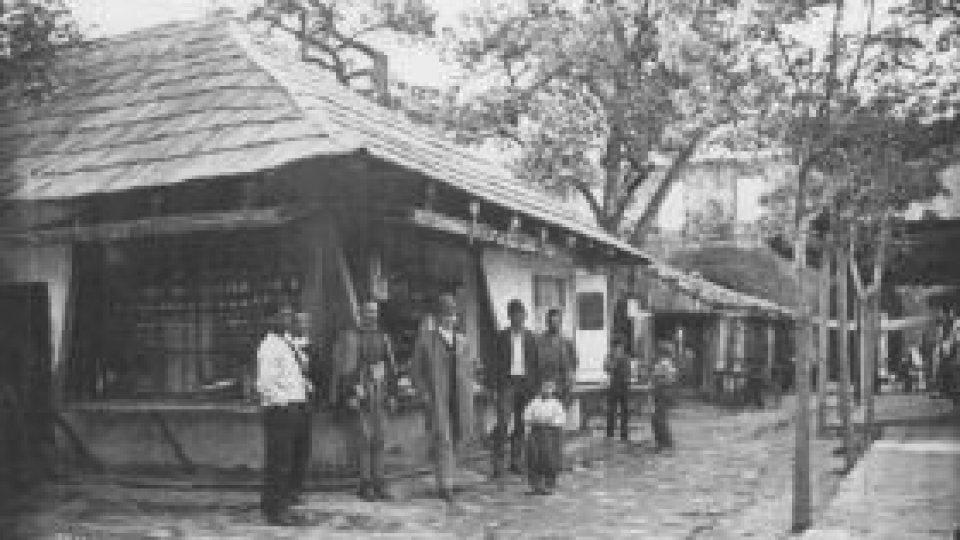

Foto: The Turkish inhabitants of the island.

Life on Ada Kaleh ran smoothly, until the end of the 1960s, when it was decided to build the Iron Gate I Hydroelectric Power Station. That meant, among other things, that the Ada Kaleh Isle would be swallowed by the waters.

That was how a world ended; how a story ended.

The island inhabitants moved, some to Orşova or Drobeta Turnu Severin, and some to Constanţa or Turkey, where they laid the basis of a neighborhood called Ada Kaleh. The move in itself was a real tragedy that was particularly trying for the elders on the island.

They were promised they would not pay for electricity, because their houses had been swallowed up when the citadel was built.

That promise was not kept, and neither were many others. They received monetary compensation to build or buy a new house, though some had brought their old one from Ada Kaleh, brick by brick.

Being poor, some took even the windows and tiles from the houses. Others packed their forefathers’ bones in bags and took them downstream, on the Şimian island, where part of the cemetery, and the citadel built by the Austrians, was moved.

The authorities intended in fact to move all the houses and their inhabitants on the Şimian island, though nobody agreed.

Hard to reach

The place is hard to reach so, if they want to go to the cemetery, sometimes it is almost impossible, as it was for us when we tried to go on the island.

Some have not given up on the idea of turning Şimian into what Ada Kaleh once was, at least from a tourist point of view. For the moment this is, as it was forty years ago, only a project.

Foto: A sketch showing the island's position on the Danube.

The Radio România Actualităţi documentary ‘Stories from Ada Kaleh’, produced by Liliana Nicolae and Liliana Bădiţă will help you find out how life changed for Ada Kaleh’s inhabitants, once they moved off the island, how they speak now, after almost forty years, learn about life on the island, the story of the largest carpet in Europe (that was a gift offered to the mosque in Ada Kaleh) and about the intention to rebuild a world that is now underwater.

We thank everyone for their support in making this documentary: Mehedinţi Frontier Police, the Iron Gates Region Museum, the National Archives - Mehedinţi Branch and the Turkish Communities in Romania.

Translated by: Diana Maftei

MA Student, MTTLC, Bucharest University